How much wilderness is enough? In Oregon, we need to do more

By Brent Fenty of Bend, Oregon. Brent is the Executive Director at Oregon Natural Desert Association.

This coming September marks the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act. It was a landmark bill when passed, representing a growing awareness that the Industrial Age was quickly changing the world around us. Therefore, for ourselves, future generations and other species that depend on wild places, we would set aside land and rivers in their natural state.

The follow-up question to this effort was and continues to be: How much is enough? The answer is clearly different for each of us. As someone who was raised in a church-going home, I've always admired the idea of tithing, and in my mind setting aside at least 10 percent of our world as wilderness is a form of tithing. Others can argue for less or -- I would hope -- more, but what I am confident of is that Oregon has not protected enough wilderness yet.

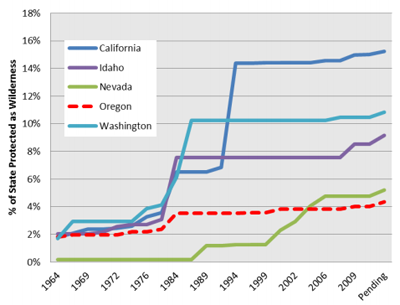

Oregon lags far behind our neighbor states in the amount of wilderness it has protected. Only 4 percent of the state is currently protected as wilderness; this is less than half of what Washington and Idaho have protected and nearly four times less than what California has protected. We clearly have a wilderness deficit.

What is also clear is that most of Oregon's wilderness is in our forests. A mere 1/3 of a percent of Oregon's high desert is currently protected as wilderness, and that is because nearly 3 million acres of public lands known as Wilderness Study Areas (WSAs) have sat in limbo for more than three decades in the throes of congressional inaction.

I have heard some suggest that the remoteness of Oregon's high desert will ensure that areas like the Owyhee Canyonlands will remain wild. This sprawling area on Oregon's eastern edge is larger than many eastern states; the Owyhee's rolling hills, roaring rivers and red-rock canyons represent the largest stretch of wildlands in the lower 48 without permanent protection. It's also a stronghold for the imperiled Greater sage-grouse and home to the largest herd of California bighorn sheep in the nation. Yet remoteness will not keep it safe. It is obvious that there is no place on land, and perhaps now even in our oceans, where development cannot reach. Already in the Owyhee Canyonlands, threats like mining, unmanaged ATV use and the prospect of oil and gas development loom on the horizon.

I recently had the opportunity to raft down the Grand Canyon. As I floated through Marble Canyon, I was startled to see bore holes, drilled into the canyon walls in preparation for a dam planned decades before. There was also paint marking where the walls of concrete were to be poured. It reinforced for me that our natural treasures only still exist because some have had the foresight to fight for their protection. As Teddy Roosevelt proclaimed upon creating what was then Grand Canyon National Monument, "I want to ask you to keep this great wonder of nature as it now is. I hope you will not have a building of any kind, not a summer cottage, a hotel or anything else, to mar the wonderful grandeur, the sublimity, the great loneliness and beauty of the canyon. Leave it as it is. You cannot improve on it."

In this 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act, I encourage you to celebrate the desert wilderness we do have and the wonderful people who had the foresight to come together to protect these areas -- Steens Mountain (14 years old), the Oregon Badlands (5 years old) and Spring Basin (5 years old). But we also need to do more for the areas that still need to be protected.

You're also welcome to join ONDA to discuss the past and envision the future of wilderness at the 27th biannual Desert Conference, Sept. 19-20 in Bend. We invite you to hear from some of the best minds in conservation, science, art and history in inspiring, thoughtful panels and discussions. Participants will also journey into the field on guided hikes. We'll confer on how we can follow the example of those early wilderness leaders and protect desert places before pressures from development overwhelm them. The ideas and energy from this gathering are important to developing effective, workable solutions for desert conservation.

|

Aug. 13, 2014

Posted in guest column. |

More Recent Posts | |

Albert Kaufman |

|

Guest Column |

|

Kari Chisholm |

|

Kari Chisholm |

Final pre-census estimate: Oregon's getting a sixth congressional seat |

Albert Kaufman |

Polluted by Money - How corporate cash corrupted one of the greenest states in America |

Guest Column |

|

Albert Kaufman |

Our Democrat Representatives in Action - What's on your wish list? |

Kari Chisholm |

|

Guest Column |

|

Kari Chisholm |

|

connect with blueoregon