Portland as a "Resilient Community"

Kyle Curtis

Is Portland ready for the "Big One?"

If there is an organization in Portland that has to do with livability and sustainability issues, chances are Jeremy O'Leary is invovled with it to some degree. With prior experiences with the city's Peak Oil Task Force, along with Transitions PDX, overseeing TheDirt.org, Portland Permaculture Guild, participating with the City's Local Energy Assurance Plan (LEAP), and also the FooDiversity group that looks at food and garden issues in East Portland. Jeremy is also an IT staffer for Multnomah County, for which he served on the steering committee for the Multnomah Food Initiative. Considering all of these organizations that he is involved with- as well as his personal interest in emergency preparedness issues- it is safe to say that Jeremy firmly has his pulse in regards to livability issues both for Portland and the surrounding region. As such, when looking for an expert to discuss these issues with, there were very few other options to contact. In a recent sit-down interview, Jeremy described the Transitions Initiative, the recent natural disasters that have rocked the country and world in recent months, and whether Portland should be considered a "resilient community" or not.

To begin with, could you describe the Transition Initiative? What is it, and what are its objectives? Would you be able to easily describe these efforts for those who are uninformed and unaware?

Sure. Let's provide a little bit of context. Transitions is a global effort started by Rob Hopkins. Rob was a permaculture instructor, and the more he learned about Peak Oil, he figured that it would be a great way to teach permaculture to deal with the effects of Peak Oil. In effect, the Transition Initiative focuses on the effects of Peak Oil, which includes "global weirding"- my preferred phrase to describe the changes of climate- as well as the economic crisis that would be created by a lack of easily available cheap energy.

But the underlying theme of the Transition Initiative is the creation of resilient communities. Very few people know that the first American city to have a Transitions "Great Unleashing" was Sandpoint, Idaho- not exactly your liberal mecca. There was a mixture of liberals and conservatives invovled in the project, with one conservative saying, "I don't particularly believe in global warming or Peak Oil, but this is simply the right thing to do." As for Transition's local history, I was personally involved with the City's Peak Oil Task Force. During this process, we looked around for models of neighborhood resiliency to deal with Peak Oil. A friend of Hopkins came to Portland and did a presentation about the Transition Initiative. It was exactly what we were looking for. The Portland Metro region is all ready a fairly advanced transition area, carrying out a lot of stuff that Transition groups all over the world talk about- gardens, bike culture, the efforts of City Repair. All of these efforts are doing great work in Portland. At the same time, a model designed for a town of 10,000 will only be scaled up so high. I should offer a cheerful disclaimer, however, and that is to acknowledge that the Transition Initiative is very much an experiment, and there is no guarantee that these efforts will succeed in dealing with life after Peak Oil. However, there is another acknowledgement that if why try to do everything by ourselves, these efforts will be too little. At the same time, if we wait for government, then it will be too late.

You used the term "resilient community." Could you provide a definition of what, exactly, a resilient community is?

There is an online definition that describes resiliency as a system that is able to withstand shock. On a personal level, if we have large-scale disruptions, resiliency describes how well can we deal with that disruption. Of course, we're never actually fully prepared for large-scale disruptions or disasters- so the discussion needs to be more about in what way we can make the recovery phase easier and be less un-prepared. A simple step to be prepared is simply knowing your neighbors and being on good terms with them. It doesn't matter how prepared we are as a community, this has little bearing if something is happening to your house. We could also look at recent disasters to see what lessons we can take away. For example, after the tsunami and nuclear meltdown in Japan, people were unable to find a bike to rent or buy. As there was no available liquid fuel, it was impossible to drive cars. So we need to be reminded- if there are trees on roads or cracks in the ground, that's a problem for cars. Not so for bikes.

For a lot of people, the extent of their emergency response planning is to have a family plan and a 72-hour kit. And that's fine. But what I'm interested in is the culture change that happens during the recovery phase. For example, after the earthquake in Christchurch, people were camping in the streets. But it was also the start of the garden season. That was what practically everyone put their attention to: tending to garden plots and growing food. This helped improve the quality of life as well as channeled the anxiety for the survivors of that disaster.

There are particular elements for the recovery phase: people need to know how to connect with each other, where the gathering places are, food and water, etc. It is necessary to backcast and see how the details fit in and what needs to be done. This is not difficult nor is it expensive to do.

In your opinion, do you believe that Portland is a "resilient community?"

In context of relationships, Portland is better than other cities. Consider our city's bicycling culture, for example. Biking helps build relationships- you're actually next to somebody on the road as opposed to be separated from each other through boxes of metal. However, I'd suggest that our emergency response effort is not as good as Japan's. Japan dealt with three emergencies simultaneously. No one is prepared for that. But consider when it snows in Portland, just how unsafe it is to drive. Not necessarily because the roads are dangerous, but because nobody in Portland knows how to drive in the snow!

Through my involvement with LEAP I have concluded that as a society, we are energy illiterate, which in turn helps cause chaos. When people throw out terms like "energy independent" it is pretty much nonsense, considering the sheer gargantuan amount of energy necessary for our society to function. Instead, a better discussion to have is to identify the minimum amount of energy necessary for our society to function- and then figure out how to insure that we have that. Figure out how we can reduce our wasteful, energy-illiterate society to reach that identified minimum energy level over a certain length of time.

So I was hoping to ask about a couple of disasters that have occurred over the past year, and whether they posed a threat to Portland or Oregon, and if so how much. You've all ready mentioned the multiple disasters faced by Japan, and their response. A lot of attention was placed on the meltdowns at the Fukushima reactor. Regardless of the fact that we are bombarded by radiation all the time anyway, did this increase of radiation pose a threat to us on the West Coast?

People are scared about radiation, and with good cause. You can't see it, or smell it. I had a friend in the Navy who worked on a ship and found out that he was exposed to a year's worth of safe exposure to radiation- within a couple of hours! There simply was no physical sensation he experienced. I don't spend that much time studying radiation. I know there was a measurable bump in the radiation levels on the West Coast, but I'm not willing to get into that too much. There was an increase in the amount of radiation levels in milk up in Washington, and that is assumed to be attributed to the Fukushima meltdown, but hasn't been directly connected.

There has also been recent new stories about how a large "megathrust" earthquake is very much over due in our region, and how that would create regional chaos as our emergency planning efforts are sorely lacking. What was your response when you heard these reports?

We average a large subduction earthquake in this area every 300 years. There was one gap that stretched from 500 to 600 years, but mostly its been 300 years on average. This large "megathrust" earthquake might occur near term, or it might be another 200 years. If we plan for community resiliency, we will be in a bit better position to respond. Again, one of the right things to do is to have a 72 hour food kit. But, how do we square this important need with the fact that a very large percentage of Oregonians simply go without enough food in the house to eat a meal every night? We need to address this gap in food access equity, and this is being addressed by the Multnomah Food Action Plan and the Portland-Multnomah Food Policy Council. While it is great to have an emergency box of food in the garage, this can only be considered "food" in the loosest sense. Which is why we need to have strong and vibrant gardens both in yards as well as community plots. Having strong and vibrant gardens makes sense in some parts of town more so than others, as in some parts of Portland the soil simply shouldn't grow any food. There are other options, such as food buying clubs partnering with such locations as schools and churches to make bulk purchases of food and process it, resulting in reduced costs for food while also ideally creating a high-volume source of emergency food at these locations. In Portland, you are within a half-mile of a school at any given point. And there are always other locations, such as shopping malls. We need to seismically upgrade our schools- this is important, and yes it will cost money and I recognize that budgets are also reduced- but these schools have kitchens as well as staff. Schools can be used as community gathering centers after an emergency, where bulk emergency food can be available. But again, we shouldn't be faced with a losing clash of priorities: We simply can't promote the stockpiling of emergency food while others deal with their own emergency of not having enough food on a nightly basis. We need to reinforce both needs simultaneously.

So, what is being done by local policy-makers, and what needs to be done, either by our elected officials or by individual and neighborhood activists?

Chris Martenson has a multiple-part web series of videos called The Crash Course, but I must warn you not to watch this series if you are prone to depression. Chris pulls no punches and he also does not fear monger. In the Crash Course, Chris offers three core beliefs:

First, the next twenty years will not look like the last twenty years. Next is the possibility that the pace and scope of change may overwhelm the ability of our key social and institutional systems to adapt. The third belief is that we do not lack the technology or understanding necessary to build a better future.

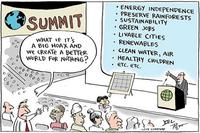

So, what needs to be done? Whenever I hear that Portland is leading sustainability, that fills me both in pride and horror. If we are number one, that's a bad sign. There has definitely been an increase in recent years of "sustainability" being used as boutique marketing versus the sustainability needed to deal with brass tacks details. Phase IV of the Portland Plan will be released in the upcoming weeks, and this will help provide a context to see where we need to deal with challenges and improve community resiliency. I wouldn't say that to be a resilient community, massive tax increases are required. Instead, we need to think through design. Again, cheap energy has made us kind of stupid, to the point where we have such strange things as apples coming to Portland from Hood River, via Los Angeles. Sometimes I feel that the best way to imagine our current society is to picture the most complex Rube Goldberg contraption as possible.

So, are there any reasons to feel optimistic about the future?

As I respond to this question, keep in mind that I have a fairly dark sense of humor. There are a few rules to keep in mind. Firs,t you can't predict the future. A hydrogen economy might be something useful for an energy source in the future. A hydrogen economy is simply another way to describe batteries and storing energy. Right now, batteries suck less than they used to, but the simply can't provide the energy demands our society needs.

Community resiliency is the right thing to do, even if our energy and economic problems go away. We need to know our neighbors and be on good terms with them- this is not only the right thing to do, it also the fun thing to do as well!

|

More Recent Posts | |

Albert Kaufman |

|

Guest Column |

|

Kari Chisholm |

|

Kari Chisholm |

Final pre-census estimate: Oregon's getting a sixth congressional seat |

Albert Kaufman |

Polluted by Money - How corporate cash corrupted one of the greenest states in America |

Guest Column |

|

Albert Kaufman |

Our Democrat Representatives in Action - What's on your wish list? |

Kari Chisholm |

|

Guest Column |

|

Kari Chisholm |

|

connect with blueoregon

9:52 a.m.

Sep 26, '11

Schools are key in many ways. Two Portland parents have formed Oregon Parents for Quake-Resistant Schools (OPQRS) to unite parent and community voices in support of seismic upgrades of Oregon public schools. Please visit and sign our petition at http://chn.ge/nCAzyq and follow us on Facebook for more information. We need your voice!

11:05 p.m.

Sep 26, '11

Thanks Kyle. Regarding the PDX Plan, the 4th and nearly final edition will be released on Oct. 6th (it is believed). For those interested in what it is ikely to include please go to the Portland Plan webpages at.

http://www.portlandonline.com/portlandlan/

See both draft #3 and the background reports.